Chapter 5.12 | The Sovereign Alibi

How international law stopped restraining power, started excusing it, and now protects the ruthless while paralyzing everyone else.

The argument that follows is not a defense of Donald Trump’s operation in Venezuela. It is not a claim that Washington has a coherent plan, that the people of Venezuela are front and center in it, or that one spectacular raid solved the problem of a criminal regime. It is an attempt to understand why a system designed to restrain abuse so often produces paralysis instead.

A week after U.S. forces seized Nicolás Maduro, Elliott Abrams observed:

In Caracas, the regime remains fully in charge. While there are concessions—some real, some merely rhetorical—for the Americans, none of them compromise the plenary power of the gang that has ruled under Chávez and Maduro. The ministers of defense and interior, both indicted drug traffickers, remain in place. Delcy Rodríguez was sworn in as interim president by her brother Jorge, who heads the National Assembly. Chavista gangs are still used to prevent or punish demonstrations. As of Saturday, just 16 of the country’s 800 political prisoners had been released. In other words, the regime is functioning internally exactly as it would have had Maduro been removed by a heart attack, and it is making the smallest concessions to Washington that it can.

I will leave the questions about who really benefits, what changes for Venezuelans, and whether the United States will back democracy or settle for oil and “stability” to others. In the weeks, months and years ahead, this will be a source of continued division in our country. Consistent with my writings in this Substack, I am more concerned with the narratives and often the hypocrisy surrounding the political discourse than the foreign policy decisions themselves.

We are told that "international law" is a shield. But look at the wreckage of the last several decades, and a different picture emerges. The system has become largely performative. It is a global theater where the UN and it’s agencies and NGOs follow a scripted routine of "concern" and "monitoring" while the world is littered with bodies. We have built an architecture that is high on rhetoric and zero on enforcement. A system that has been rewired to protect the lawbreaker and paralyze the law-abiding.

The primary engine of this paralysis is the UN Security Council Veto. What was originally designed as a safeguard to prevent World War III, has evolved into a permanent suit of armor for the world’s most ruthless actors.

When the Security Council is paralyzed by repeated Russian and Chinese vetoes on crises like Syria and Ukraine, or by American vetoes on Israel‑related resolutions the rest of the UN system does not fall silent.1 Instead, it becomes politicized and performative. Because the Council cannot act, the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council talk. They pass non‑binding resolutions that feel like “law” but carry no weight. This creates a dangerous illusion of progress. We appoint fact‑finding missions to Venezuela and special rapporteurs to Iran, collecting mountains of evidence that everyone knows will almost certainly never lead to a courtroom.

This is the core of the performative trap:

The bureaucrats get to feel they are “doing something” by writing 400‑page reports.

The dictators get to ignore the reports because they know their patron on the Security Council will veto any real consequence.

The victims are left with a “record of their suffering” and a tombstone.

In this vacuum of enforcement, the “identity trap” thrives. Since the law cannot be enforced equally, it is instead applied selectively. On much of the political left, where this trap is most visible, international law is no longer about the act (murder, torture, starvation); it is about the actor. If the actor is viewed as an “anti‑imperialist” or a “historical victim,” the system’s inherent paralysis is reframed as a moral virtue, a defense of “sovereignty” against the “bullying” of the West.

I. The Promise and the Contradiction

The capture of Nicolás Maduro brought this into sharp focus. Almost immediately, the story shifted from a starving nation under the control of an illegitimate leader to a legalistic mourning of violated “sovereignty”.

Consider this statement by Ravina Shamdasani, spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner, speaking to journalists in Geneva. Rejecting the US justification for intervention based on Maduro’s “longstanding and appalling” human rights record, she insisted:2

Accountability for human rights violations cannot be achieved by unilateral military intervention in violation of international law. Far from being a victory for human rights, this military intervention, which is in contravention of Venezuelan sovereignty and the UN Charter, damages the architecture of international security…And this is a point that the Secretary-General has also made.

This raises an obvious question: if “accountability cannot be achieved by unilateral military intervention,” how exactly is it meant to be achieved when the international community refuses to act?

II. Venezuela and the Sovereign Alibi

What has the UN actually done since Chávez took control of Venezuela in 1999? This headline in an Amnesty International Report says it all “Decisive action by UN Human Rights Council supports victims and signals at perpetrators that the world is watching them”

The ‘decisive action’ in question was the Council’s decision to renew the mandate of its Independent International Fact‑Finding Mission and the OHCHR presence in Venezuela, allowing investigators to keep documenting abuses and reporting to Geneva.

And the world did watch. The UN monitored and reported as Chávez concentrated power. Under Maduro, the Human Rights Council eventually created a “fact‑finding” mission and OHCHR issued detailed reports describing extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detention and possible crimes against humanity, while UN agencies coordinated underfunded humanitarian and refugee responses as nearly eight million Venezuelans fled.

What it never did was impose enforcement measures or meaningful costs on the regime. Sovereignty, reinforced by great-power politics, insulated Caracas from consequence. The world watched while atrocities accumulated. Accountability existed only on paper.

This paralysis is the final, decayed stage of the Hobbesian bargain3. Thomas Hobbes described the “Sovereign” in his seminal 1651 work Leviathan as a “Mortal God” who holds absolute power to maintain peace and order within society created for one specific purpose: to rescue human beings from a state of nature where life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." For Hobbes, the Sovereign’s authority was absolute only because it was the sole guarantor of peace and security.

But the international system has performed a grotesque surgery on this logic. It has kept the Hobbesian shield of absolute sovereignty for the dictator while discarding the Hobbesian requirement that the dictator actually protect his people. We are now asked to respect the "Sovereignty" of regimes that have returned their citizens to the very state of nature the state was invented to abolish.

This is the sovereign alibi in action. But sovereignty alone does not explain the paralysis. The deeper reason is ideological sorting. The question is not whether the system has rules, but who the rules are for.

Critics will argue that this sorting is a necessary correction for centuries of Western dominance. They claim that "blind law” was never actually blind, but a tool of the powerful. However, the result of this correction is a total inversion of justice: by trying to protect the "marginalized" state, the system ends up protecting the dictator who is currently marginalizing his own people. Certain regimes are treated as historical victims whose sovereignty must not be breached, no matter the scale of their crimes. Others are treated as moral aggressors whose sovereignty is endlessly negotiable. That sorting determines whether violence is condemned as atrocity or contextualized as grievance.

III. Iran and the IRGC: Proof It’s Systemic

Iran shows that this is not a regional failure or a uniquely American dilemma.

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran has experienced several major waves of rebellion. While the specific “flashpoints” have evolved from student rights to economic despair and, most recently, women’s autonomy, the government’s response has followed a consistent pattern: total internet blackouts, mass arrests, and the use of lethal force by the Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) and Basij militia.

Sadly, the international response has also followed a predicable pattern. Monitoring. Reporting. Statements of concern. Special rapporteurs. And, in a grotesque inversion, the same regime responsible for repression was appointed to chair a major UN Human Rights Council forum and the Council’s Asia-Pacific Group.

What the UN did not include was enforcement. The evidence was overwhelming. The repression was open. Yet sovereignty and “anti-imperialist” framing once again converted brutality into complexity. The world watched. The IRGC learned: documentation is survivable. Accountability is optional. This is the "Identity Trap" at its most lethal. Because the IRGC positions itself as the vanguard of an anti-Western identity, its internal repression is treated as a "complex domestic matter." The law becomes a suicide pact because it refuses to see a perpetrator as a perpetrator if they use the correct ideological password.

As mass demonstrations spread across Iran in early 2026, the regime’s response followed a grimly familiar script. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps moved to crush them, demonstrators were shot, imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Women were beaten to death for defying dress codes. Thousands disappeared into detention. As of this writing, it is believed that over 12,000 have been murdered by the IRGC since the start of this open rebellion. President Trump has publicly warned that if the regime killed protesters, there would be consequences4. Once blood began to flow, the WSJ reported that his advisers floated a menu of options: offensive cyber operations to blind Iran’s internal command and control, disruption of state broadcasting, covert sharing of real‑time intelligence on Basij deployments to help demonstrators avoid ambush, financial support for striking oil workers, even flooding the country with satellite internet terminals to pierce the blackout.

Those discussions underscore the core point here. Even a U.S. administration that is demonstrably less squeamish about using force is not calling in armored divisions or promising a Baghdad‑style occupation. It is trying to find ways to raise the cost of repression without owning the entire outcome of Iran’s internal uprising.

Meanwhile, in the multilateral arena, the regime that orders the shootings continues to enjoy the full protections of “sovereignty”. Its officials sit in UN forums. Its diplomats trade on the language of non‑intervention and “anti‑imperialism.” Its violence is endlessly contextualized by history, sanctions, and Western sins. The message to the IRGC is the same one Maduro received for years: documentation is survivable. Statements are survivable. What is not survivable is a serious shift in the balance of power.

That is the systemic failure. Revolutionary regimes that position themselves as victims of Western power are treated as untouchable subjects of law. Their “sovereignty” is absolute. Their violence is “complex.” Intervention is reflexively denounced as colonial aggression, even when the only people asking for help are the regime’s own citizens being shot in the streets.

Commentators like Andrew Yang have captured the moral urgency of this moment in Iran. He describes a regime that bankrupts its own economy, brutalizes women for dress‑code violations, sponsors Hamas and Hezbollah, and now guns down protesters in the streets after shutting off the internet and he asks what America is for if not to help bring such a tyranny down. That instinct is not wrong; the evil is real, and the courage of Iranians facing live fire is undeniable.

But this is exactly where the gap between moral impulse and international structure widens. The same system that has spent decades contextualizing the IRGC and shielding Tehran behind “sovereignty” will be first in line to declare almost any serious U.S. support for the uprising “illegal,” while offering Iranians little more than statements and rapporteurs. The question is not whether the regime deserves to fall. It is whether a legal and political order that treats its victims as abstractions and its oppressors as “stakeholders” is capable of helping them at all or only of condemning the democracies that try.

IV. Israel: Proof It’s Asymmetric

The inversion becomes unmistakable when the same legal framework is applied to Israel.

When Israel uses force to defend its citizens against terror groups like Hamas, legality suddenly becomes absolute and unforgiving. Every action is parsed as potential criminality. Intent is presumed malign. Sovereignty is treated as conditional. We have built a world in which the identity of the actor matters more than the substance of the act. A democratic state defending its citizens is presumed guilty. A terror group or anti-Western autocrat is presumed contextual.

A counter-perspective suggests that Israel is judged more harshly because it is a "Western-style democracy," and therefore should be held to higher standards.5 But this logic is itself a form of discrimination. It implies that people living under autocracies deserve less protection from the law, and that "ruthless" actors should be given a moral discount simply because they don't claim to be part of the liberal order.

The same system that treats the IRGC as a complicated regional stakeholder treats a democratic state under constant attack as a presumptive violator. At the UN General Assembly and Human Rights Council, Israel is the target of more country‑specific resolutions than any other state, while far more brutal regimes often face little or no sustained censure. The law does not disappear. It changes direction.

The language that seals this asymmetry is always the same: “international consensus.” Ask almost any major institution about Israel and the answer comes back, as if it were an axiom, that there is a global consensus that the territories are “illegally occupied,” that settlements are per se unlawful, that Israel’s presence is governed by a law of occupation whose meaning is beyond serious dispute. The same bodies are far more cautious when asked to pronounce on Russia’s borders after Crimea or on China’s claims in the South China Sea. Consensus, it turns out, hardens around Israel and dissolves elsewhere.

Yet even on the narrow question of borders, the story is messier than the catechism allows. The 1949 armistice agreements explicitly stated that the so‑called Green Line merely marked where armies happened to stand when the guns fell silent, “without prejudice to future territorial settlements or boundary lines,” and Arab negotiators insisted that language be included. Jordan’s later annexation of the West Bank was recognized by almost no one, including most Arab states. When Israel captured the same territory in a defensive war in 1967, it was taking control of an area that had never been widely accepted as Jordanian sovereign soil. Even the principle of uti possidetis juris, which the international system has applied to freeze colonial borders in Africa and Latin America, has been invoked by jurists to argue that Israel inherited the Mandate borders at independence, a claim that is treated as serious everywhere except in this one case.

None of this proves that every Israeli policy is wise or just. It does show that the “international consensus” is not a neutral reading of law handed down from on high. It is a political choice about which doctrines to emphasize and which to ignore, and about where legal ambiguity is tolerated and where it is declared heresy. It requires acknowledging that it is judged by standards that are not applied elsewhere. When the victims of repression sit in judgment and the targets of terrorism are treated as moral aggressors, the problem is not law. It is asymmetry.

This asymmetry is not limited to how foreign regimes are judged. It appears just as clearly in how Western leaders themselves are treated.

Actions taken under President Barack Obama that raised serious questions of sovereignty and international law were widely contextualized, and absorbed into the language of responsibility. Drone campaigns across multiple countries and the intervention in Libya were defended as reluctant but necessary uses of force. Similar legal ambiguities under President Donald Trump are treated as uniquely dangerous violations of the international order, cited as evidence that norms themselves were collapsing.

The issue is not which president was right. The issue is that legality was framed differently depending on who acted. International law functioned as a flexible context for some and an absolute constraint for others. Identity preceded judgment.

This is the identity trap in full view. Once actors are sorted into oppressor and oppressed, the law ceases to bind everyone equally. It becomes a vocabulary for excusing chosen clients and prosecuting chosen enemies.

That inversion is not an aberration. It is the operating system.

A system that treats “sovereignty” as untouchable (even when led by an illegitimate actor) and identity as exculpatory cannot survive contact with ruthless actors.

V. Rebuttal: “But Look at the Progress We’ve Made”

At this point, defenders of the system raise what they consider the decisive objection.

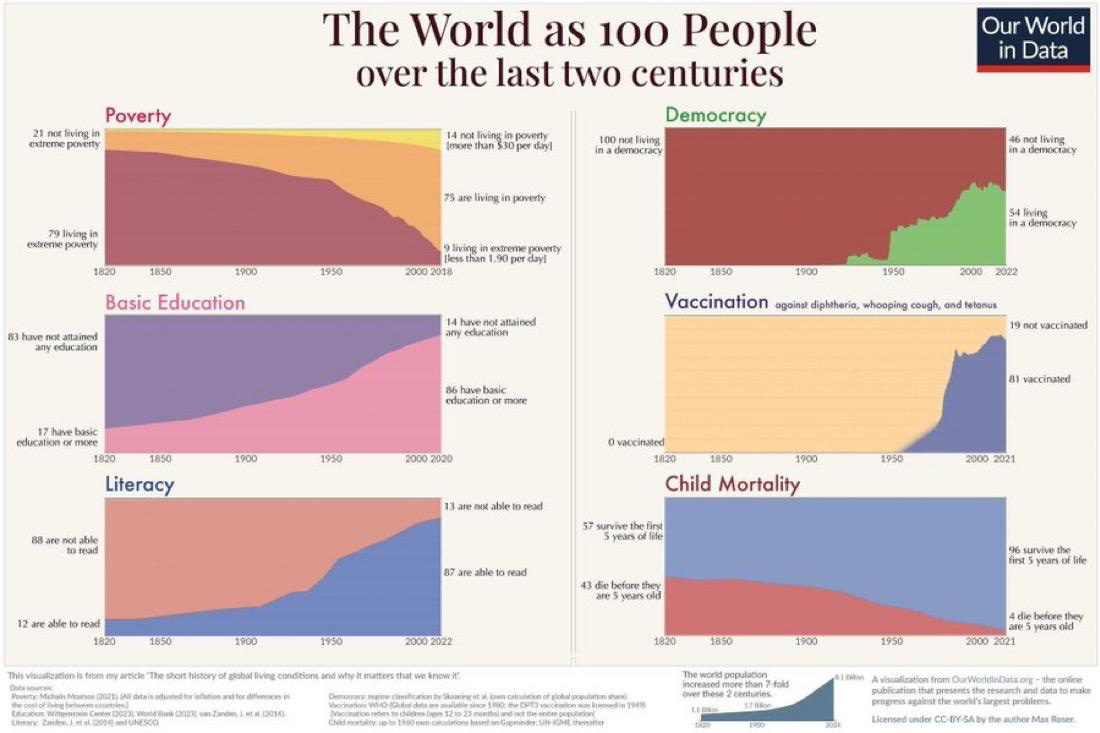

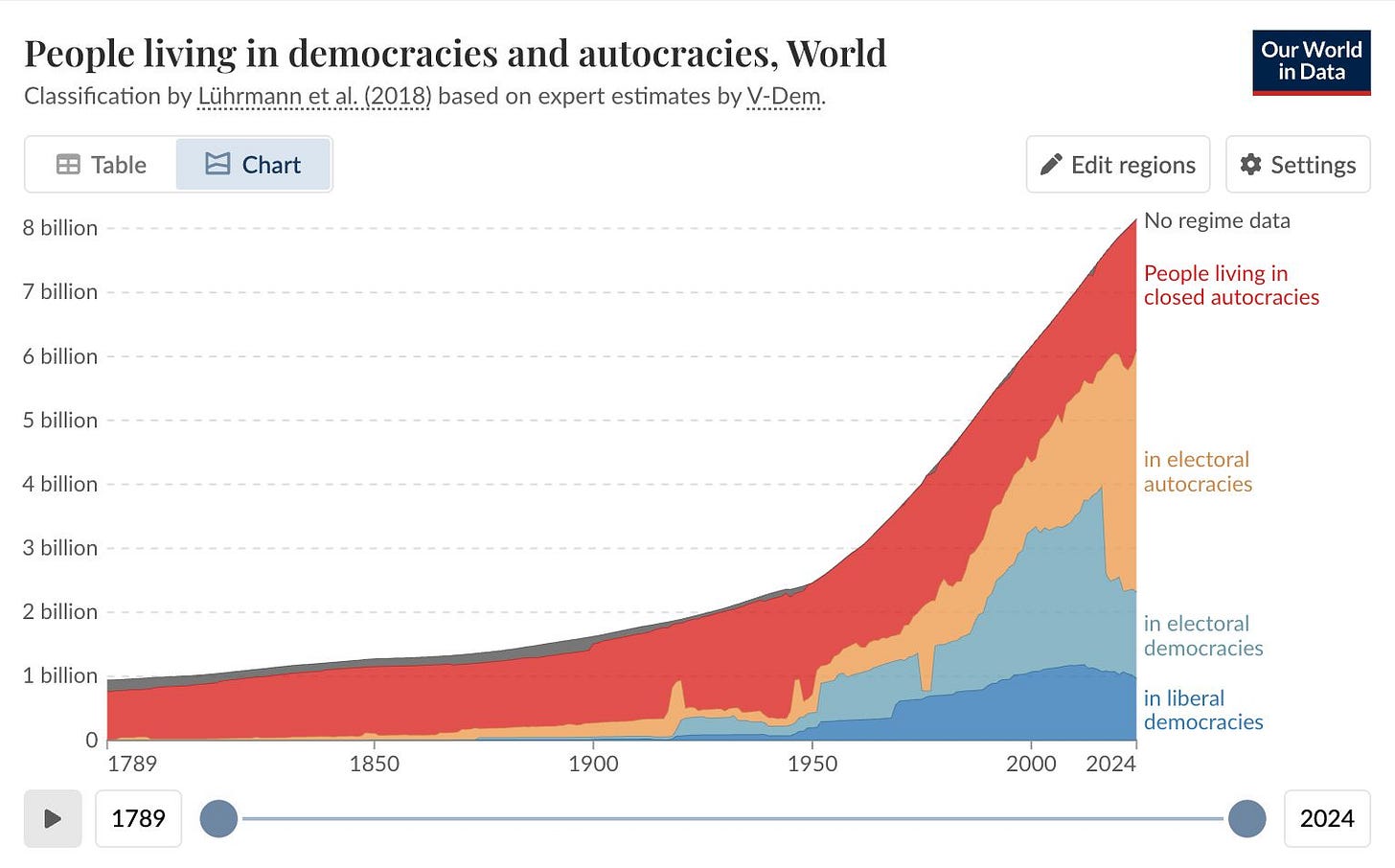

When confronted with these failures, defenders of the system often change the subject. They point to charts showing dramatic improvements in living standards.

These gains are real.

But they are also frequently misattributed. Prosperity tracks industrialization and trade far more closely than it tracks any particular set of legal institutions in New York or Geneva. Growth is not moral legitimacy.

Citing material progress to excuse institutional paralysis is not compassion. It is deflection. If we accept that autocracies are "succeeding" because they provide growth, we are falling into the ultimate identity trap: the idea that certain populations living under autocratic rule neither need nor want the "universal" rights the West claims to cherish.

By country count, democracies may still slightly outnumber autocracies in international institutions. By population, the picture flips completely. According to the 2025 V-Dem report, the world now has fewer democracies (88) than autocracies (91) for the first time in over two decades. Roughly 72% of the global population about 5.8 billion people now lives under autocratic rule. The level of democracy experienced by the average person has fallen to levels not seen since 1985.

Particularly dangerous is the rise of “grey‑zone” regimes: electoral autocracies and backsliding democracies like Mexico and Indonesia. Elections exist, but accountability is hollowed out from within. When these regimes slide, they destabilize entire regions while retaining the formal protections of sovereignty and international legitimacy. The identity trap rewards this drift.6

The problem is not just moral inconsistency. It is that the global conditions that once masked these failures are disappearing.

VI. The World That’s Coming: Deglobalization and Power

Peter Zeihan’s 2022 best seller “The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization―The Collapse of Globalization and Its Aftermath” paints a picture of the world that makes this even starker. The era of effortless globalization he describes is ending. Supply chains are regionalizing. Demographic collapse is hollowing out workforces. Energy security is becoming a local, not global, question again. The “order” that made container ships, cheap credit, and open sea‑lanes feel like facts of nature depended on a very specific configuration of American power and political will. That configuration is fraying.

If Zeihan’s analysis is broadly correct, de‑globalization means that geography and hard power reassert themselves. Chokepoints, food systems, manufacturing bases, and demographics matter more than communiqués in New York. A world like that will not be governed by resolutions. It will be governed by who can keep trade routes open, who can guarantee energy flows, who can absorb shocks, and who can credibly deter predators in their region. If law is not anchored in that reality, it will simply be ignored. The risk of "stripping away the alibis" is that we might find nothing underneath. If the "Identity Trap" has corrupted the system's core, then removing it might reveal that the "International Community" was always just a collection of interests wrapped in a flag of convenience.

If international law is not anchored in the reality of power and deterrence, it becomes a cage for the principled and armor for the ruthless. The Monroe Doctrine is not just nostalgia; it is one way of describing what survival may require for the United States in such a world.

The answer to the charade of international law is not to abolish law. It is to strip away the alibis that have grown around it. To admit where it failed. To rebuild a framework where law binds everyone, not just those willing to abide by it, and more importantly enforced, by force if needed.

That will require hard choices. Where to stay. Where to leave. Where to act alone. Where to bind ourselves to rules even when they bite. The alternative to the current system is not chaos, but narrower coalitions, clearer mandates, and enforceable commitments.

VII. When America Walks Away

In a system that lacks enforcement, responsibility does not disappear. It concentrates.

The world is experiencing a surge in violence not seen since the post-World War II era. The year 2024 marked a grim new record: the highest number of state-based armed conflicts in over seven decades.

Against this backdrop, the United States has begun asking a hard question: should it continue underwriting an architecture that no longer delivers accountability.

According to Peace Research Institute Oslo (Prio):

A staggering 61 conflicts were recorded across 36 countries last year, according to PRIO’s Conflict Trends: A Global Overview report. “This is not just a spike – it’s a structural shift. The world today is far more violent, and far more fragmented, than it was a decade ago,” warned Siri Aas Rustad, Research Director at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and lead author of the report. “Now is not the time for the United States – or any global power – to retreat from international engagement. Isolationism in the face of rising global violence would be a profound mistake with long-term human life consequences.”

On January 7, 2026, a Presidential Memorandum directed the US to withdrawal from 66 international organizations, including 31 UN entities. This move is not simply about budgets. It is about legitimacy.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio framed it bluntly in “Ending the Charade of Wasteful International Organizations”:

The United States has played a central role in shaping the international order. From the Monroe Doctrine which allowed nations in our region to flourish free from interference outside of our hemisphere, to our pivotal role in the establishment of the United Nations, to serving as the primary security guarantor under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and as the world’s largest humanitarian donor, America’s leadership has been unquestionable. Leadership requires difficult choices, and the ability to recognize when the institutions created to promote peace, prosperity and liberty have become obstacles to those goals. What we term the “international system” is now overrun with hundreds of opaque international organizations, many with overlapping mandates, duplicative actions, ineffective outputs, and poor financial and ethical governance. Even those that once performed useful functions have increasingly become inefficient bureaucracies, platforms for politicized activism or instruments contrary to our nation’s best interests. Not only do these institutions not deliver results, they obstruct action by those who wish to address these problems. The era of writing blank checks to international bureaucracies is over.

While critics see a retreat from leadership, the charade is real. Participation confers legitimacy even when results are absent and victims are invisible. Critics of the 2026 withdrawal argue that the U.S. is merely creating its own "Identity Trap" one where "American Interest" is the only metric of truth. But the counter to that is clear: if the existing institutions already use identity to excuse tyranny, then "staying at the table" is not an act of diplomacy; it is an act of complicity.

For the United States, this is not an abstract debate. A de‑globalizing world means the American role moves back toward what the Monroe Doctrine (1823) originally implied: securing the Western Hemisphere, policing key sea‑lanes, and choosing carefully where commitments are sustainable rather than pretending to referee everywhere. It also means that walking away from every multilateral forum is self‑defeating. In a more fractured world, the coalitions that still work will be the ones built on real capabilities and shared interests, not slogans. They will still need rules, even if they are narrower and more honest than the universalist promises of the past.

None of this is clean. None of it is risk‑free. American power has its own ugly record when it forgets law and constraint. But a world of shrinking demographics, weaponized trade, and opportunistic autocracies will not be made safer by institutions that only constrain those already inclined to play fair. In Zeihan’s world, as in ours, order survives only where power, geography, and some credible notion of justice line up.

I would argue that walking away from 66 international organizations, is not a retreat from leadership. It is a refusal to continue underwriting a charade. Leadership sometimes means building, but it also means knowing when a structure has rotted beyond repair. When the “international system” protects those who forcibly interfere with the liberty of millions, it has ceased to serve its purpose.

VIII. Conclusion: A Suicide Pact

The patterns are now too consistent to dismiss as coincidence. When democracies act, every decision is litigated in the language of law. When tyrants or armed movements brutalize their own people, the same language stretches to accommodate “context,” “root causes,” “complexity,” and “anti-imperialism.” The result is not neutrality. It is a hierarchy of excuse.

In a de‑globalizing world, the cost of that paralysis rises. As supply chains fracture, demographics deteriorate, and regional blocs test alternatives to the dollar7, power is shifting back toward geography, hard capacity, and the willingness to enforce red lines. A legal order that cannot reckon with those facts will not constrain the ruthless; it will only bind the states still willing to take law seriously.

The choice is not between law and lawlessness. It is between a legal architecture that treats sovereignty and identity as unchallengeable shields, and one that is honest about the conditions under which rules can actually be enforced. The former rewards the very actors most determined to exploit it. The latter would mean fewer promises, narrower institutions, harder decisions about where to stay and where to walk away, and a willingness to judge friends and adversaries by the same standards.

The ultimate rebuttal to this entire piece is the fear of the "Unknown." If we break the "Identity Trap," we must be prepared for a world where we, too, are judged by the acts we commit, rather than the values we claim to hold.

The identity trap promises moral purity. What it delivers is a world where procedure survives and people do not. The sovereign alibi claims to defend order. What it produces is impunity.

In the world that is coming, clinging to both is not virtue.

It is a suicide pact.

If this resonates, subscribe for more on fairness. What's your view? Share below.

Since 2011, Russia has cast at least 19 vetoes in the Security Council, 14 of them on Syria alone, often joined by China, blocking resolutions on chemical weapons, sanctions, ceasefires and cross‑border aid. Russia has also repeatedly vetoed resolutions condemning its aggression against Ukraine, forcing the General Assembly to take up the issue in emergency sessions instead. On the other side, the United States has used its veto to block multiple resolutions on Israel and Gaza; by late 2025 it had cast six vetoes in less than two years on ceasefire and protection‑of‑civilians texts that otherwise had near‑unanimous Council support. In each of these files, the machinery outside the Council kept moving: the Human Rights Council renewed and expanded a fact‑finding mission on Venezuela, created and extended a special rapporteur and fact‑finding mission on Iran that documented crimes against humanity during the Woman Life Freedom protests, and produced hundreds of pages of findings. But without Council action, those mechanisms have generated very little in the way of concrete accountability, illustrating how veto‑driven deadlock at the top produces a pattern of highly politicized, largely symbolic activity everywhere else.

The UN human rights office, OHCHR, was expelled from Venezuela in February 2024, following its consistent reporting on the deteriorating situation there. Independent probes commissioned by the Human Rights Council have also detailed grave and ongoing abuses against opponents of the country’s ruling party. And yet none of this altered the basic power structure in Caracas or stopped the abuses they documented.

A Hobbesian bargain(or social contract) is the fundamental agreement where individuals surrender some natural freedoms to an absolute sovereign in exchange for security and order, escaping the brutal “state of nature” (life without government) characterized by constant fear, violence, and a “war of all against all,” ensuring self-preservation and peace. This pact establishes a powerful government (the Leviathan) whose primary role is to enforce rules, maintain stability, and protect citizens from each other and external threats, making life predictable and allowing society to flourish.

As reported by Eli Lake:

Trump risks looking like one of his predecessors, Barack Obama, if he doesn’t follow through. This is what happened in August 2013. Obama had warned for a year that if Syria’s then-tyrant, Bashar al-Assad, used chemical weapons against the rebels, the U.S. would militarily intervene. When Assad finally dropped sarin gas on a rebel stronghold outside of Damascus, Obama flinched. He asked for an authorization of force from Congress, and ended up not entering the war. Obama’s failure to enforce his own red line on chemical weapons had dire implications for the balance of power, not just in the Middle East but throughout the world. Only seven months later, Russia invaded and later annexed Crimea from Ukraine, the first salvo in a war that has continued to this day. In the Middle East, Russia established air bases in Syria in 2015. Trump’s decision to join Israel’s war against Iran’s regime in June and take out the country’s main nuclear facilities is further evidence that Trump’s words should not be ignored.

Must watch:

Of particular concern, Democracy without Borders notes:

The United States received special attention in the 2025 V-Dem report, which identified the country as undergoing the ”fastest evolving episode of autocratization the USA has been through in modern history”. Although the data and metrics used for the report only extend through the end of 2024, researchers still included alarming findings regarding the U.S. following the election of Donald Trump, who is testing the limits of executive power at an “unprecedented scale”.

The U.S. president has employed several typical autocratic tactics such as expanding executive authority, weakening the power of Congress, launching attacks on independent institutions, undermining oversight bodies and the media, and purging and dismantling state institutions.

As I’ve noted in previous chapters, this should be of particular concern.

This definition of liberty has always resonated with me:

Liberty means being free to make your own choices about your own life and therefore what you do with your body and your property ought to be up to you, provided, however, that other people must not forcibly interfere with your liberty, and you must not forcibly interfere with theirs.

Slowly but surely, over the past five decades, our political parties have centered themselves on a definition of liberty and “conservatism” that no longer aligns with that definition.

The stakes are no longer just moral. The economic siege of the West has moved from theory to infrastructure. Power is not only military. It is financial, industrial, and geographic. On October 31, 2025, the BRICS+ bloc launched the “Unit” pilot, a gold-anchored settlement instrument designed to bypass the dollar. This digital trade currency, partially backed by physical gold and BRICS currencies, signals a structural shift toward a multipolar financial world where the “rules-based order” can be ignored by anyone with enough gold and a regional trade bloc. In this world, the Monroe Doctrine is not nostalgia; it is survival. Ending a regime that starved its population and partnered with cartels is a just outcome even if the legal footing is, as it almost always is in moments of crisis, imperfect.