Chapter 5.11 | Trump’s Cannabis Rescheduling EO: Is it Good Policy or a "Ploy for the Stoner Vote”.

An evidence‑based look at the Executive Order, Schedule III, and how modern prohibitionists distort data to defend a failed status quo.

In May 2024, the Miami Herald published a heavily edited version of this editorial. After the news on December 18th that President Trump had signed an Executive Order directing federal agencies to reclassify marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act “Increasing Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research” the WSJ editorial board published a flawed piece titled “Trump Goes for the Stoner Vote: Rescheduling pot sends the wrong message to vulnerable young brains”. I felt compelled to update and republish the full text of my original essay.

As Co‑Founder and Managing Partner of Entourage Effect Capital, a venture firm that has deployed more than $200 million into over 70 cannabis companies across the legal U.S. market, I have had a front‑row seat to how federal policy actually operates on the ground. I have watched promising, well‑regulated businesses struggle under punitive tax treatment and banking constraints that make it easier for illicit operators to thrive than compliant ones. I have also seen the human side: investor capital evaporated, entrepreneurs bankrupted, employees laid off, and communities denied the economic and public‑health benefits that come from moving cannabis out of the shadows and into a transparent, regulated system.

Rescheduling Marijuana Isn’t Radical. Pretending Prohibition Works Is.

Cannabis prohibition has been an abject failure. It has wasted billions of taxpayer dollars with nothing to show outside of outdated policies rooted in discrimination and the destruction of individuals’ and their families’ lives. Advocates of continued prohibition paint cannabis legalization as a resounding negative that creates dangerous and harmful outcomes for American society. Current and former public officials have amplified their disdain for reform, relying upon cherry-picked data and biased analyses from disputed studies. Their conclusions lack sufficient exploration into whether cannabis’s perceived risks morally or practically justify the criminalization of the plant.

Commentary, including the December 20th Wall Street Journal editorial board opinion criticizing President Trump’s decision to reschedule cannabis, repeats the same pattern: highlight the real risks of cannabis, especially for youth, while ignoring the failures and harms of prohibition, the federal government’s own updated science, and any evidence that cuts the other way. Rescheduling is portrayed as a political play for “stoner” votes rather than what it actually is: a belated move to align federal policy with current evidence and to enable more rigorous regulation and research

Cannabis is currently listed under Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, designated for drugs displaying no medical use and a high potential for abuse. It sits in the same category as heroin and is deemed more dangerous than Schedule II drugs such as cocaine, fentanyl, morphine and oxycodone. To continue to believe that cannabis should remain under Schedule I is absurd and undermines the credibility of those arguing to maintain federal prohibition. Back in 1988, Francis Young, the DEA’s chief administrative law judge, believed interdrug comparisons were relevant in assessing cannabis’ classification. He observed, “Marijuana, in its natural form, is one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man. There are simply no credible medical reports to suggest that consuming marijuana has caused a single death.”

UCSF integrative oncologist Donald Abrams, one of the few researchers to obtain government-approved supplies of cannabis for human trials, stated that “cannabis has medical uses” and it’s “clear from anthropological and archaeological evidence that cannabis has been used as a medicine for thousands of years.”

What rescheduling actually does (and doesn’t)

Moving cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III does not legalize state medical or adult‑use markets under federal law; manufacture and distribution outside DEA/FDA‑regulated channels remain federal crimes under the Controlled Substances Act. It does three main things:

Acknowledge that cannabis has accepted medical uses and a lower abuse risk than Schedule I/II drugs, consistent with the Department of Health and Human Services’ 2023 review.1

Remove the 280E tax penalty so that state‑licensed operators are taxed like other businesses, rather than at confiscatory effective rates.2

Lower research barriers so that more rigorous clinical trials and FDA‑style approvals become feasible.

That is closer to treating cannabis like other controlled medicines with benefits and risks, not to declaring it harmless or fully legal.

The DEA’s failed policies have allowed an illicit cannabis market to exist and thrive, with sales estimated at $60 billion to $75 billion. Prohibition proponents advocate against legalization while continuing to allow illegal cannabis dispensaries to flourish and jeopardize the health and safety of the public.

We live in a time where our government is failing to do their job representing the will of the people at a time when 70% of Americans support legalization. The Wall Street Journal point to recent defeats of adult‑use ballot measures in Florida, North Dakota and South Dakota as evidence that legalization has “failed” at the ballot box. But that leaves out two crucial facts. First, these measures often received majority support—Florida’s Amendment 3, for example, won about 56% of the vote but fell short of the 60% supermajority the state requires for constitutional amendments. Second, since 2012, voters in dozens of states have approved medical and adult‑use reforms, so the national map shows a steady expansion of legal access with pockets of resistance, not a broad popular rejection.

It strains credulity to argue that cannabis should be classified as a Schedule I drug, and this incongruity should raise questions of credibility about the current regulatory environment. It is time for the federal government to legalize cannabis and put in place common sense policies that will ensure a safe and secure legal cannabis market. Legal operations ensure cannabis is lab tested and protect our children from the illicit market, where products are laced with fentanyl and other dangerous drugs, toxic pesticides, and heavy metals.

Economic and criminal justice failures

Consider the substantial cost-savings our government could incur if it were to tax and regulate cannabis, rather than needlessly spend billions of dollars enforcing its prohibition.

Harvard economist Jeffrey Miron predicts legalizing cannabis would save $7.7 billion per year in government expenditure. In Crimes of Indiscretion: Marijuana Arrests in the United States, Jon Gettman supports that conclusion estimating that $3.7 billion is spent by the police on enforcement, $853 million by the courts, and $3.1 billion in corrections. Such expenditures have resulted in mass incarceration and increased violence without substantially affecting drug availability. Moreover, despite evidence that usage rates are similar, African Americans and Latinos are nearly four times more likely to be arrested for cannabis than white Americans. From 2001 to 2010 alone, there were over 8 million cannabis arrests in the U.S. – 88% of which were for simple possession.

By contrast, on an annual basis, it’s estimated that federal legalization of cannabis could bring in nearly $8.5 billion in state tax revenue alone. Lawmakers have instead chosen to forgo this opportunity.

Federal prohibition fuels the illicit market

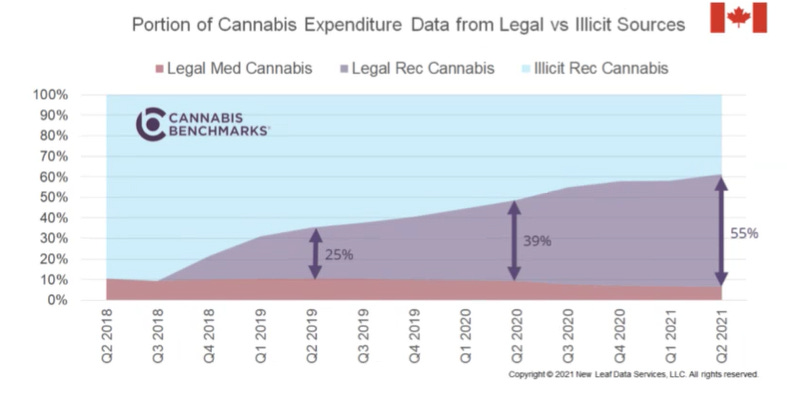

Upon halting the latest push to legalize adult-use cannabis in Virginia, Governor Glen Youngkin argued that legalization “does not eliminate the illegal black-market sale of cannabis.” Evidence suggests the opposite. In Canada, where they have federally legalized cannabis, data suggests that as the legal market grows it is taking market share away from the illicit market.

Eradicating the illicit market requires the development of a competitive legal market that adequately serves the adult population. But with legal state markets hindered by federal policy, prices are driven by high taxes and slow licensing rollouts (i.e. New York). This can be remedied by eliminating excessive taxation and providing more opportunities for businesses to break into the market, including those run by individuals with legacy experience. Those criminally punished for something that should never have been a crime must be granted amnesty.

Youth, potency, and public health deserve serious, not selective, concern

The WSJ is right about one thing: cannabis today is often more potent than in the 1990s, and heavy adolescent use is linked to real risks (cannabis use disorder), psychotic symptoms in vulnerable individuals, impaired driving, and emergency‑room visits. The question is what policy tools best reduce those harms.

Prohibitionists cite correlational studies on IQ, psychosis, or cardiovascular events as if they prove that any cannabis use causes these outcomes, while often ignoring the authors’ own cautions that causality has not been established and that better, prospective data are needed. They also point to ED visits or poison‑control calls without distinguishing mild intoxication events from severe or lasting harm.

It is my opinion that a regulated adult‑use framework with enforced age limits, product testing, potency labeling, and targeted education is better suited to protecting teens and young adults than an illicit market that sells untested, high‑dose products to anyone with cash. The choice is not “harmless” versus “dangerous”; it is whether we manage known risks transparently or continue to outsource them to unregulated dealers.

Cannabis & health: causation vs. correlation

In a March 2024 op-ed, William Barr and John Walters, the former U.S. Attorney General and former Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, asserted that legalizing cannabis was a mistake. In so doing, as Jacob Sullum opines, they “ignore the benefits of legalization and systematically exaggerate its costs.”

In that same month, the House Republican Policy Committee described cannabis as a “crime” and “gateway drug” that leads to “violence, depression and suicide.” Along similar lines, Barr and Walters state that we don’t have “a full understanding of [cannabis’] health risks.” The pair draw conclusions based on incomplete or intentionally misleading statistics, utilizing relative risk percentages while ignoring absolute risk in order to exaggerate outcomes, and failing to distinguish between correlation and causation. For example, they argue “studies have found that teens who regularly use marijuana experience an eight-point decrease in IQ.” The study in question is of 1,000 kids in New Zealand who “frequently” smoke cannabis before their 18th birthday. This impact is actually a direct result of a failure to regulate. Under any regulatory scheme adopted, teen use would be strictly prohibited in a legalized market that mandates ID checks.

Similarly, Barr and Walters reference “long lasting effects” on mental health, referencing an article published by the Heritage Foundation about users from a 2016 study. The study was based upon continued cannabis use in patients with psychosis, furthering their conflation of causation and correlation. As Charles Ksir and Carl Hart report in their analysis of that same study, “the interpretation extends beyond the available data” and “the meta-analysis was based on correlational studies.” They go on to say that “each study points out that causation has not been shown, and we should not allow the consistency of these correlational findings to substitute for actual evidence of causality.”

Flawed arguments from Barr and Walters go on: “States with liberal cannabis laws have seen a significant increase in marijuana-related ER visits,” but the article provides zero evidence of actual injury or harm. They write, “one in three people who use marijuana become addicted,” sourcing the CDC. In actuality, the agency does not state that they are addicted; instead, they reference “marijuana use disorder.” When compared to other Scheduled substances like heroin and cocaine, the risks and harm of cannabis addiction are minimal.

Barr and Walters continue to ignore interdrug comparisons, likely because data suggests that cannabis presents less risk than many legal substances. Compare it to alcohol (an unscheduled substance): Mortality risk from alcohol use is ~114 times greater than that of cannabis; the CDC attributes 1,600+ U.S. deaths per year to alcohol poisoning, while there has never been a fatal cannabis overdose; organ damage associated with alcohol abuse can be lethal at levels nowhere near that of the most frequent cannabis users; alcohol leads to more violence than cannabis; and driving ability is more impaired by alcohol than cannabis. Similarly, more than 400,000 deaths each year are attributed to tobacco smoking, while cannabis is nontoxic and cannot cause death by overdose.

On cardiovascular risk, they rely on a self-reported study which acknowledges that initial research needs “prospective cohort studies” to properly examine the association. Moreover, references to relative risks are misleading by amplifying the actual danger posed by a particular behavior.

How prohibitionist arguments including the WSJ editorial cherry‑pick risk

Like the Barr/Walters op‑ed, the WSJ editorial leans heavily on worst‑case anecdotes fatal crashes with THC in toxicology screens, psychotic reactions to mislabeled edibles, or ED visits while omitting any denominator. It does not distinguish relative risk (for example, elevated odds ratios in observational studies) from absolute risk, nor does it meaningfully compare cannabis harms with legal substances such as alcohol and tobacco, which cause far higher mortality and social damage.

They also ignore the federal government’s own updated science. In recommending Schedule III, HHS concluded that cannabis has “currently accepted medical use” and that:

The vast majority of individuals who use marijuana are doing so in a manner that does not lead to dangerous outcomes to themselves or others.

That sentence never appears in prohibitionist commentary, despite being central to the current rescheduling decision.

Banking, 280E, and “helping marijuana companies”

Critics complain that rescheduling “helps marijuana companies do more business” by allowing normal tax deductions. But 280E does not distinguish between responsible, state‑licensed operators and bad actors; it simply over‑taxes the entire legal industry while leaving untaxed, unregulated illicit operators untouched. If the goal is to move commerce out of basements and into accountable, inspected businesses that card customers and test products, aligning tax treatment with other regulated industries is not a giveaway. It is basic policy coherence.

Looking to the future

Cannabis’ risks and benefits should be relentlessly explored, publicized, and impartially applied to policy while upholding the rights of adults to make their own decisions. To enhance freedoms, generate wealth, and promote the health and well-being of Americans, we must lean into science, appropriate government and industry with a commitment to truth and practicality.

Editorials that focus only on harms, ignore the failures and inequities of prohibition, and dismiss the federal government’s own scientific findings do not promote honest debate; they prolong a status quo that is costly, discriminatory, and less protective of youth than a well‑regulated legal market.

It is critical to acknowledge both the potential risks and benefits of cannabis use, while also recognizing the need for further research to fill the current gaps in our understanding. Therefore, discussions around cannabis legalization and its potential health impacts should be grounded in a balanced review of the available evidence, considering the limitations of current studies and the broader context of cannabis use within society. This approach ensures a more nuanced and informed public debate that can better guide policy and personal decisions.

While HHS noted that there are high levels of cannabis abuse, they also found that the effects of this abuse led to substantially less harmful outcomes when compared to other controlled substances. In determining a drug’s potential for abuse, HHS considers four criteria: (a) evidence that individuals take the drug in harmful amounts; (b) if there is a diversion of the drug from legitimate drug channels; (c) if individuals take the drug without medical advice; and (d) the drug’s similar properties to other drugs determined to have a potential for abuse. HHS found that serious effects associated with cannabis abuse were consistently less frequent and serious than other Schedule I and II drugs like heroin, cocaine, and oxycodone. HHS considered data including poison control reports, emergency department visits, overdoses, and substance use disorders.

Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 280E is a U.S. federal tax provision that prohibits businesses from deducting ordinary and necessary business expenses from gross income if the business is engaged in the “trafficking” of controlled substances (specifically Schedule I and II drugs under the Controlled Substances Act), even if those businesses are legal under state law.

Key Details of Section 280E

Origin: Section 280E was enacted by Congress in 1982 in response to a Tax Court case (Edmondson v. Commissioner) where a convicted cocaine dealer was allowed to claim deductions for his illegal drug business expenses. Congress intended to prevent drug dealers from benefiting from standard business expense deductions on public policy grounds.

Application to Cannabis: Because cannabis remains classified as a Schedule I controlled substance under federal law, state-legal cannabis businesses (such as cultivators, manufacturers, and dispensaries) are subject to Section 280E. This creates a major financial burden, as these businesses cannot deduct most operating costs like rent, utilities, marketing, and employee wages.

Impact: The result is that cannabis businesses have a much higher effective federal tax rate, often 70% or more, compared to the typical 21-30% for other legal enterprises. This significantly impacts profitability and cash flow.

Sole Exception: Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): The only expenses cannabis businesses are permitted to deduct are those directly related to the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). This includes direct costs for raw materials, labor involved in cultivation or production, and packaging materials. Non-production related costs, such as salaries for sales staff or general office supplies, are not deductible